Brazil's deficit isn't the result of economic necessity. It's the result of a political decision: spending more, promising more, nationalizing more—while the population's future is unceremoniously mortgaged.

In this post, we will examine how Brazil reached alarming levels of nominal deficit and public debt, according to a recent study by BTG Pactual, and what this reveals about the Brazilian government's inability to adapt to a sustainable economy.

👉 Read also: The Culture of Deficit: The State That Never Learns

Brazil has one of the largest deficits on the planet

According to a report published by G1 on January 14, 2025 (link to the article), based on a study by BTG Pactual, Brazil will have, in 2024 and 2025, one of the largest nominal deficits in the world.

The projections are blunt:

- Nominal deficit of 7.8% of GDP in 2024

- Nominal deficit of 8.6% of GDP in 2025

Among the major global economies—both developed and emerging—Brazil is second only to Bolivia in fiscal mismanagement. Meanwhile, projected gross debt is expected to reach 86% of GDP by 2026, demonstrating a trajectory of increasing debt.

The study warns: even after the pandemic shock, most countries reduced their deficits. Brazil, however, is following the opposite path, deteriorating its public finances at a faster rate than the average for emerging and even developed economies.

The new normal: deficit as state policy

Historically, high deficits should be seen as exceptions—temporary responses to specific crises. In Brazil, however, the deficit has become a structural policy.

The strategy is clear:

- Expanding social spending and state investment without rebalancing real revenue

- Relying on uncertain extraordinary revenues to meet goals

- Postpone structural cuts to privileges, subsidies and inefficiencies

According to BTG's own report, the current government estimates that it will meet the target of zero primary deficit in 2024 — but based on R$ 178 billion in uncertain revenues, including unguaranteed revenues and measures that are difficult to implement politically.

Meanwhile, the organic growth of public debt, associated with the perception of high risk, puts pressure on interest rates and makes the economic environment more unstable.

The fiscal vicious cycle explained

High debt imposes immediate and perverse costs:

- High fiscal risk → Higher risk premium

- Higher risk premium → Higher interest rates demanded by investors

- Higher interest rates → More debt service expenses

- More debt spending → Less room for productive investment

Every extra real spent without any basis not only worsens the problem but also fuels it.

BTG highlights that part of the cost of debt is driven by the expansionary fiscal policy itself, which puts pressure on inflation, requires higher basic interest rates (Selic), and increases the cost of financing for the government itself.

The False Dilemma: Growth at Any Price

Official rhetoric often argues that "spending more" boosts growth. In the short term, it may even work—artificially. But without solid fiscal foundations, growth is illusory, fragile, and paves the way for deeper crises.

The report indicates that, even with growth above 3.5% in 2024, the deficit will remain exorbitant, and the debt will continue to rise. This reveals that growing without fiscal discipline doesn't solve the problem — it just postpones the collapse.

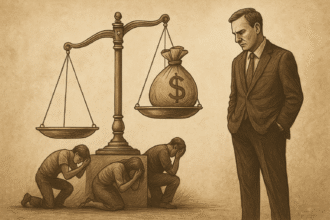

The invisible effect: inflation, devaluation and impoverishment

In addition to debt, the unstable fiscal scenario directly impacts people's pockets:

- Puts pressure on the exchange rate (devaluation of the real)

- Makes imported products more expensive

- It feeds domestic inflation

- Raises the cost of living

The study itself mentions that the real has already reached levels above R$ 6 in recent times — and should continue to be pressured by the perception of risk.

The political elite can protect itself. Those who can't are workers, entrepreneurs, and small investors—all condemned to foot the bill.

Conclusion: the State that does not cut is the State that condemns

BTG's diagnosis is clear: Brazil is experiencing an escalation of debt that, although aggravated by global factors, is mostly self-inflicted.

High deficits and rising debt are not inevitable phenomena. They are the result of deliberate political choices: the choice not to cut privileges, the choice to expand the state apparatus, the choice to sustain a power structure at the expense of the future.

While the government insists on postponing reforms and selling accounting illusions, the country approaches, year after year, a new breaking point.

The nominal deficit is more than just a number in the BTG report — is the portrait of a State that refuses to mature.